Design

Amonkhet: Fact and Fiction

Ancient Egypt has captured the Western popular imagination like few parts of our past ever have. It’s the oldest, but far from the only, great empire to emerge in Africa. Even though Egypt-inspired fiction Tomb Raider to Moon Knight treats it like an isolated phenomenon, Egypt is part of Africa and a component of the history of the second-largest continent on Earth, not its own thing out in the Aether. It’s very easy to forget that.

Don’t.

Amonkhet, Magic’s foray into Ancient Egypt, is the only plane to center African history, religion, and stories in the world’s first trading card game. I’m not Egyptian myself (Pennsylvania Dutch), but I study Egyptian history as a graduate student, so I’d like to look at how well Magic captured the heart of Ancient Eygpt.

What’s in a Name?

Let’s start with one of the things Wizards did best: Amonkhet’s creature types.

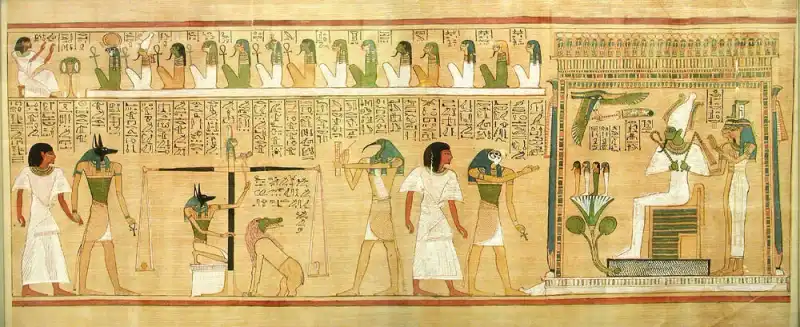

As a fantasy game, Magic thrives on the supernatural, and therefore we’ll treat Amonkhet as a reflection of Egyptian religious and philosophical beliefs. Egypt’s spiritual world was full of terrifying devourers, wise but harsh judges of souls, and benevolent guardians. While the white-winged angels and goat-horned demons of the set match Western pop-cultural and Christian religious depictions closely, I can hardly blame Wizards (who has to keep creature type designs coherent across sets), and Amonkhet’s angels and demons are only a bird head and knife away from fitting right in to the Book of the Dead:

Then there are the animal-human hybrids. Sphinxes, the merger of pharaoh and lion meant to scare off evil spirits and guard the sacred grounds of the temple, make an appearance. (The riddling ones are Greek.) Even Amonkhet’s mundane denizens have animal heads on human bodies, much like the animal-headed gods of the Egyptian pantheon. Falcon-headed Ra, the sun, soars above the Earth, while Hathor acts as the nurturing maternal cow (and, like the cow, is terrifying in anger). This reflects on the mundane creatures in the set: charging bulls, loyal dogs, nimble birds.

Amonkhet block introduces eight gods with Aetherdrift adding four more. The insect-headed gods of HOU don’t really match well on Egyptian ideas of divinity - they resemble the Ten Plagues of Exodus more than they resemble Egyptian deities. The original Amonkhet gods have the closest analogues with Egyptian ones: Oketra is Bastet, protective feline goddess of harvests; Kefnet is Thoth, ibis-headed guardian of knowledge; Bontu has Sobek’s crocodile head but is clearly the war god Montu; Hazoret is Bastet’s wrathful counterpart Sakhmet, the lady of destruction and pestilence. (Sakhmet means “she who is mighty”.) Rhonas stands alone without a clear analogue; the Egyptians did not venerate the untamed wild. If anything, he is closest to the chaos god Seth.

Another excellent flavor win are the cartouches. The pharaohs of Egypt had five names, each associated with a particular deity and each imbued with powerful symbolic meaning. The king would choose these names at his ascension (though one was usually just his birth name), setting a political and religious agenda for his rule. When the citizens of the plane unlock magic power through the taking on of these names, it closely matches ancient practice.

(Incidentally, only two of those royal names were written in cartouches. Two were left outside any container and one was written within a stylized palace facade called a serekh. The Egyptian word for what we call a cartouche is shen; cartouche is French, so called by Napoleon’s soldiers for the part of Egyptian inscriptions that looked like their bullet cartridges.)

Finally, Amonkhet avoids two great pitfalls common to many Western depictions of ancient Egypt: orientalism and colorism. Orientalism is the belief in an unchanging, backwards, despotic, unnuanced East stretching from North Africa to East Asia and everywhere in between. Colorism is a bias towards light skin colors. As an example of both, think of the 2003 film The Last Samurai, in which a old-fashioned Japan can only be changed by white Americans, either by the introduction of modern weaponry (by the antagonists) or the mastery and refinement of their traditions (by the white, foreign protagonist).

In stark contrast, we meet Amonkhet at a time of great dynamism, as one political order gives way to another and the ruling powers are rapidly deposed. To the credit of Wizards’ art team, Amonkhet’s humans display the diversity of skin tones accurate to both ancient and modern Egypt. The hair and clothing styling is historically plausible, too, if the armor is somewhat fantastical. Samut in particular looks like she could have jumped right off of the walls of a Theban tomb.

The Mummy Returns… again… again

Where Amonkhet falters, in my view, is in a dependence on the tropes of Egyptomania rather than Egypt’s own practices. Egyptomania peaked in the Victorian and Edwardian obsessions with ancient Egypt, but its legacy is alive and well in the present. Mummies are probably the most prominent feature of this aesthetic, and Amonkhet is no exception. It’s true that the Egyptians mummified their dead (though this treatment was restricted to royals and the ultra-rich, especially earlier in Egyptian history) and that they placed a great emphasis on funerary ritual. In popular culture, mummification is often the subject of macabre fascination and associated with a Christian-like afterlife for the recipient. However, Egyptian funerary rites were much more about the preservation of the spirit and its ability to continue to interact with the living world. While I understand Wizards’ desire to follow Shadow over Innistrad’s zombies with Amonkhet’s, ancient Egypt’s views on afterlife would be closer to Spirits-matter, or perhaps a morbid-type mechanic that provides value out of investing in the dead.

The Egyptomanical idea of the “pharaoh’s curse” has been a fascination for the public ever since Lord Carnarvon, financier of the excavation of Tut’s tomb and owner of the mansion in Downton Abbey, died of blood poisoning from an infected mosquito bite shortly after the tomb’s public discovery. Alongside wild misinterpretations of tomb inscriptions,1 Edwardian journalists concocted a narrative of vengeful spirits taking revenge on hapless archaeologists (one that frequently feeds into orientalist and mysticist narratives around Ancient Egypt more generally). As much as I love the curse subtype, including it here spreads dangerous misinformation about the nature of Egyptology and of the ancient Egyptians’ own beliefs about their tombs.

Real-Life Crossovers

Amonkhet contains a few other little references to Ancient Egypt, especially its history. Hapatra is only a few letters off from the real-life figure Cleopatra VII, last pharaoh of Egypt. Cleopatra was a brilliant woman and able politician who met her downfall after backing the wrong horse in the last gasp of the Roman Republic. Later writers villainized her as a seductress, but every ancient ruler engaged in political marriages. That Hapatra is the vizier of poisons is a reference to her suicide, probably by poison, that Cleopatra chose instead of being paraded through Rome as a prisoner of war. (Viziers, for their part, were the highest officials of the Egyptian government, halfway between chief justice and prime minister, but the word is an anachronism derived from Persian; in Egyptian, it’s tchaty).

Temmet is Tutankhamun (King Tut), the other pharaoh of Egypt famous enough that Wizards risked name-dropping them in a Magic set. His rule was unremarkable, a decade of rule from ages 9 to 19 mostly at the mercy of his advisors, dying of an infected broken leg before he could truly make his mark on history. A stroke of luck meant that his tomb was barely looted in ancient times, allowing modern archaeologists to find it intact and leading to a surge of interest in Egyptian art and history.

Ammit is a minor divinity of Egyptian religion that is singled out for inclusion. She was part-lion, part-hippo, and part-crocodile; her task was to devour the heart of anyone unworthy of joining with the god Osiris after death, ending their existence forever (you can spot her in the Book of the Dead image above). Her name means “she who devours”, which sounds terrifying - until you realize it’s an onomatopoeia. “Amamam” is how the Egyptians heard chewing, just like we use “Omnomnom”, and the -t at the end is how the Egyptians render “she who”. She Who Om-noms.

There are also a few references to more modern pop culture on the plane that are a bit out of place. Dune finds a home here (perhaps fitting, because Frank Herbert uses Ancient Egyptian words in Children of Dune). Much more jarring are the motorcycles and bug helicopters added to the setting by Aetherdrift. That blending of ancient and modern worked poorly and took away from much of what Wizards had built in the first two visits to the plane.

Of course, it’s not just the flavor that made Amonkhet interesting. There’s a whole draft environment of the block that we don’t have time to cover here but I have lots of feelings about. So keep an eye out for my next article where we will finally answer the question: are cartouches good in Limited?

- A few ancient Egyptian tombs have warnings in them, as do tombs in a number of cultures. In Egypt, they mostly concerned the introduction of ritual impurity into the tomb, either of which could have disturbed the afterlife of the owner. They were probably directed at the literate priests who maintained the tomb, not (likely illiterate) tomb robbers.↩